Wild Geese by Mary Oliver

You do not have to be good.

You do not have to walk on your knees

for a hundred miles through the desert repenting.

You only have to let the soft animal of your body

love what it loves.

Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine.

Meanwhile the world goes on.

Meanwhile the sun and the clear pebbles of the rain

are moving across the landscapes,

over the prairies and the deep trees,

the mountains and the rivers.

Meanwhile the wild geese, high in the clean blue air,

are heading home again.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely,

the world offers itself to your imagination,

calls to you like the wild geese, harsh and exciting

over and over announcing your place

in the family of things.

---

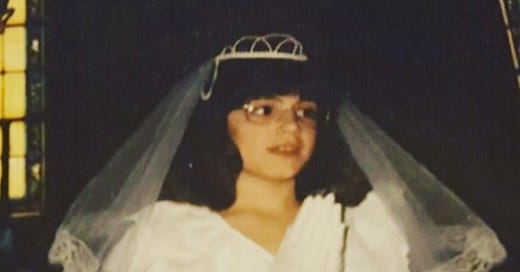

When I was about six years old I had my first confession. I was raised Catholic, and I was raised on the idea of good and evil. At six years old apparently, I had committed enough sins to warrant a visit to the priest. Whatever I had done, whatever evil I had committed as a first grader, it was enough to keep me from heaven.

And heaven was more than just eternal happiness. Heaven was where my grandparents were, my great grandparents, and someday my parents and my brother. My aunts and uncles and cousins. To be kept out of heaven sounded awful. And in the Catholic Church when you are kept out of heaven, but not quite bad enough to go to hell, you are in an in-between place called purgatory.

In my imagination, purgatory was like being locked outside of the most amazing party, and everyone you loved was there, but you couldn’t go in. I was not about to let this happen to me.

So I did everything I could do as a six year old to make sure that I would go straight to heaven. Following the ten commandments, this was a big one. Wearing a scapular tucked underneath my shirt (mine was a cloth necklace with pictures of the holy family). I was told that if I died wearing my scapular, my devotion would absolve me of my sins.

I also prayed, sometimes in the morning, usually before meals, and always at night. Now I lay me down to sleep, I pray to the Lord my soul to keep, and if I should die before I wake, I pray to the Lord my soul to take. As a child I assumed, since I was taught this prayer by adults who knew how the world worked, that people of all ages must be dying in their sleep all the time, without any warning.

So I was thrilled when I got to go to confession. This was gonna be it for me. For the last six years I had accumulated sins too numerous to even really remember. So I chose to go with some easy ones: fighting with my brother, not doing what I was told by my parents and teachers, being mean to the other kids, sneaking candy and soda. I knew that once I confessed, the slate would be wiped clean. And I was never going to sin again. I was gonna be good.

I was in Catholic school at the time and my whole class got to go together. And so we went, led by Sister Marietta, to the church next door. And then we each, one by one, stepped inside what looked like a large wooden box with two sides separated by a blue curtain.

Forgive me Father for I have sinned. There was a priest sitting there and I did my best to recount my moral failings. The priest waved his hand and said I was forgiven. He instructed me on the prayers to say in penance and told me to let the next person in.

I remember my friends and I afterwards, we felt so light and free we stretched our arms out and flew through the parking lot back to school. In my memory, when I think about it, it feels as if I am actually flying. If goodness had a feeling, than that would be it. Flying, as the poem says, like a wild goose through the sky.

Many years later, when I read that Mary Oliver poem, I had already figured out that I was a perpetual sinner. Goodness, it seemed, was beyond me. And heaven, well, I wasn’t even sure it existed anymore. But think of what she says in that poem. You do not have to be good.

This is Universalism. It is the belief that at the end of life, everyone—no matter who we are or what we have done—is reconciled to the Holy. You don’t have to confess. You do not have to walk on your knees for a hundred miles through the desert, repenting. You only have to let the soft animal of your body love what it loves.

This Divine Love. It is radical acceptance, of ourselves, of our bodies, of who and what we love. There is no God in the sky judging us, hovering in the clouds, looking for reasons to condemn us or separate us from those we love. We are allowed to love what we love. And nothing that is love can be evil.

Tell me about despair, yours, and I will tell you mine. In Mary Oliver’s poem, even despair can be holy. Even despair is sacred. Even at our lowest, we are never out of the circle. We are never cast out. Meanwhile the world goes on.

Whoever you are, no matter how lonely, the world offers itself to your imagination. And I love this line because even being lonely can sometimes feel like a failure. If we were good we wouldn’t be lonely. If we were good we’d have more friends, know how to connect, be well liked and sought out and part of a big joyous family. But we don’t have to be perfect. We only have to love what we love. That is enough. Even in our loneliness, even in our despair, we only have to love.

You do not have to be good to feel free enough to fly through the parking lot like a wild goose. You do not need anyone to absolve you. You, in all your flaws and imperfections, loving who and what you love, will be reconciled.

And as the poem says, the world goes on. This is such humble grace, that love is available to us at any moment and there is nothing required. We are inherently worthy.

Something interesting happens when deep down we truly feel inherently worthy. Out of that place—our sense of self-worth, our understanding that we matter, that we are loved—out of that sense of connection to the great web of life springs a desire to do good. When we feel good deep down inside and know we are loved, we naturally, instinctively want to share it. When we feel connected we want to do good.

This is exactly the opposite of what my religion taught me growing up. I was taught that you had to do good to be worthy. But now I believe that when we as humans are allowed to connect with that source of love and goodness inside, we feel empowered to do good things for others, we feel inspired to do good things for the world.

And we do not have to walk on our knees for a hundred miles through the desert, repenting. We only have to connect with love. And then we don’t worry so much about being good. Instead we start looking for ways that we can do good.

But here’s my confession: I never actually said the prayers the priest told me to say that day. I mean I tried. But I was six. And I could only kind of remember half of one. And the other was boring. And I didn’t want to say it ten times. In the end I just pretended that I said the prayers.

So you see I had barely stepped out the door when I was already beset with sin again. But it was too late because the world had offered itself to my imagination. And I flew through that parking lot with my friends, feeling loved and forgiven. Perhaps I wouldn’t be good. But eventually I would figure out how to do good. And that to me has been much more meaningful.

We belong here, each one of us, in the world, on this earth. No matter what anyone has told us about our failings and mistakes. No matter what we’ve been told about goodness and perfection. We belong here. We are enough. We are inherently worthy of all the world has to offer. And we have every right, whether we say our prayers or not, to live from that love that rests deep within us and to respond to the world with all that we are as it announces our place in the family of things.

I remember that day in the parking lot. I was one of those friends. I was there.

We were skipping and jumping and singing. “I’ve got that joy, joy, joy, joy, down in my heart. Where? Down in my heart.” Flying is an apt description. Elation would be another good one.

I don’t exactly know how I stumbled across your Substack. I sorta kinda recognized a name, yours, that I maybe remembered. Didn’t know your middle name was Star. Very cool of your folks that one.

But I’ll never forget that first communion. It was one of the best days of my life. It was such a high. I wonder if I haven’t been chasing that dragon spiritually ever since.

Regardless, you’re a wonderful writer. And thank you for the trip down memory lane.